Why you feel stuck and what you can do about it

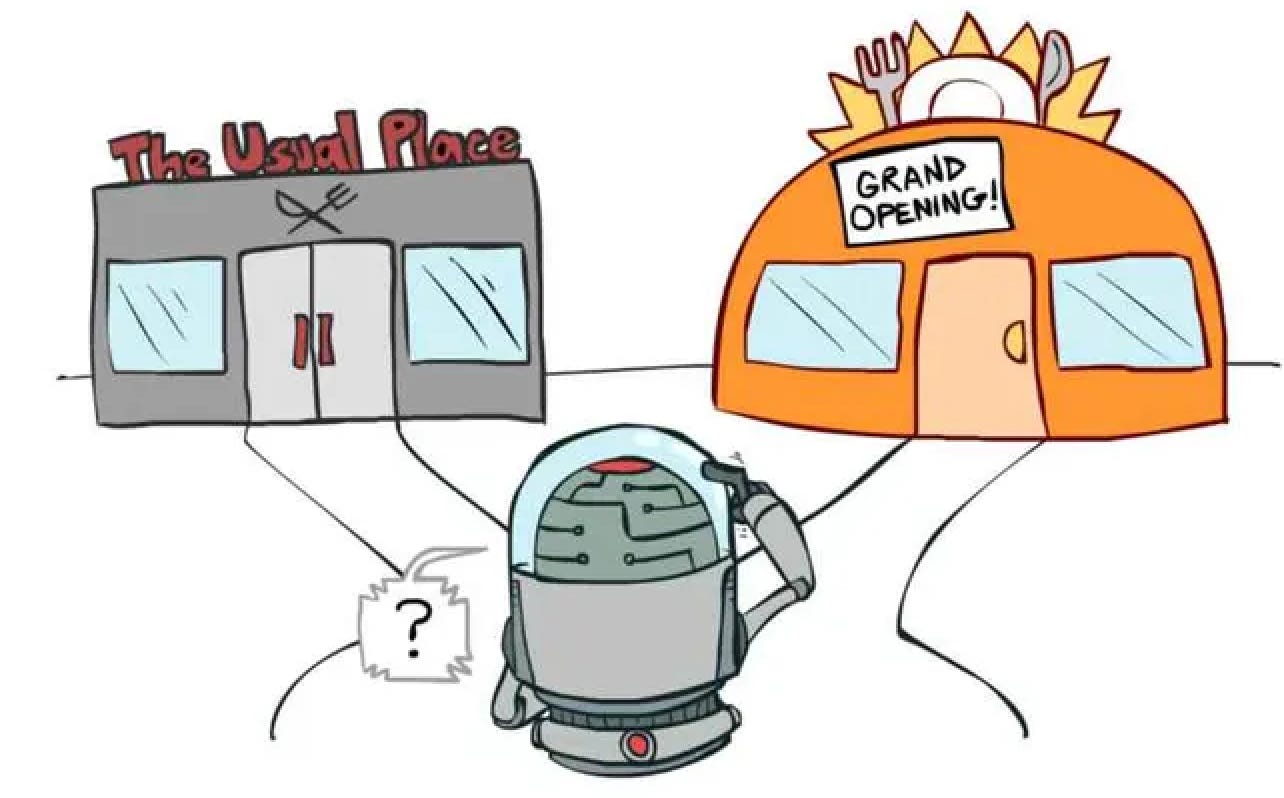

Understanding the exploration-exploitation trade-off

We often hear the term ‘comfort zone’. But what does it really mean?

Say you started a new job in a new city – a heady challenge that young age gave you the zeal to take on. You adjusted to the culture, customs and aced your company induction, rising ranks in no time. The experience was truly rewarding, resulting in steady personal and professional growth. And then the growth plateaus (not on paper since you still got promoted and moved to a bigger house) and you stop feeling challenged. You want to move to that new city that promises better quality of life or take up a job in that buzzy sector but find yourself feeling ‘stuck’. Even within the same organization, you find yourself unable to move to a new vertical or experiment and set up new systems. At this point, you think it can’t get any worse, but the comfort and dwindling utility of everyday life even starts distracting you from immediate and routine tasks.

While this feeling may be new to the affected individual, the evolutionary human systems that underly it have existed for millions of years. For long periods of history, humans were content with their (then) newfound ability to repeat patterns and behaviors that had previously resulted in a successful search for food and energy (exploitation). As predators evolved, their ability to set ‘traps’ remarkably enhanced in a very short span. Cognizant of this tendency of humans to repeat rewarding behaviors, predators were able to replace the reward (food) with claws. In response, humans took their next major evolutionary step. They developed the ability to break away from these patterns by considering and choosing alternatives, which allowed them to pursue previously uncharted paths (exploration).

Even today, the only way to stop feeling ‘stuck’ is to readjust the balance of exploration and exploitation.

Numerous studies (such as this one and this one) have defined and explained the two terms. For this article, we will make a reference to a more general definition, consistent with explanations across domains such as management and neuroscience – “Exploration entails disengaging from the current task to enable experimentation, flexibility, discovery, and innovation. Exploitation aims at optimizing the performance of a certain task and is associated with high-level engagement, selection, refinement, choice, production, and efficiency.”

Striking a balance or modulating between these two competing cognitive exercises is key. But before discussing how one can do this, let’s first call out what every exploration-exploitation tradeoff has in common – the element of search. Search in the context of this tradeoff is better understood as first, the act of seeking a goal under uncertainty (exploration). And then, reacting to changes in the environment, and refining our behaviors based on feedback (exploitation). This allows us to readjust our path towards the goal, or the goal itself.

The tradeoff presents itself in various facets of our lives:

1) Routine decisions such as what to eat for lunch, or what movie to watch – do we eat what we love (exploit) or try something new (explore)? Do we watch the big budget movie that our friends watched (exploit) or the new independent movie (explore)?

2) Big decisions such as do we continue living in the same city (exploit) or move to a new one (explore)?

3) At our jobs, do we allocate time to new projects (explore), or expand the old ones (exploit)?

4) Choosing between learning through acquiring more depth (exploit) or width (explore)

5) Do we go back to that beach town we love (exploit) or travel to the mountains (explore)?

The quality of our decisions is dependent on foresight, focus and adaptability. The initial phase of decision-making requires the ability to simulate each path and its end results. The latter phase requires us stay on course while adapting to changes in the environment. A person that has both these abilities in abundance and can effectively switch between and reconcile exploration and exploitation will invariably make better quality decisions!

Role of emotion

James March in his seminal work on the subject of exploration and exploitation described the returns from exploitation as “positive, proximate, and predictable”. This makes sense considering how exploitation entails refinement of existing knowledge and imitating best practices. On the other hand, exploration involves experimentation and a higher risk threshold since its returns are “uncertain, distant, and often negative.” Consequently, switching from exploitation to exploration is extremely hard.

Even when we know that an alternative has potential for a much larger bounty, choosing it still feels tough given the emotional cost and discomfort involved. And that’s the funny thing about emotions; they impair (or sometimes augment) our ability to take decisions based solely on practical considerations and probability assessment. Awareness of this fact can be liberating. Imagine the next time you feel anxious before changing course. You know you have prepared well and considered all possible ramifications. Still, you cannot shake away the anxiousness. At this point, it would be wrong to associate the anxiousness with anything other than the uncertainty involved. Equating it to ill-preparedness and deciding not to pursue the alternative would be a travesty!

This is precisely why people wait for deterioration (beyond repair) of the current situation or path before deciding to consider alternatives. At that point, the emotional cost is much lesser, and hence the choice feels easier.

Role of dopamine

Dopamine is often mislabeled as the ‘pleasure chemical’ and it is easy to see why. When we expect a set of actions to yield success (in our pursuit of pleasure), the release of dopamine helps us stay on course, and undertake and repeat these actions (reinforcement learning in humans). However, the pursuit of something cannot be equated to its enjoyment. And since dopamine is not associated with the actual enjoyment of the reward or pleasure (that is the role of serotonin), it’s characterization as a ‘pleasure chemical’ is not accurate. Simply put, dopamine helps us engage in reward or pleasure-seeking behaviors but does not leave us feeling satiated when we get what we sought.

When unsuccessful in our pursuit, dopamine release is adjusted based on a corresponding adjustment of ‘our expectations’ – more dopamine is released when the probability of reward is higher and less, when probability is adjusted downwards.

What is described above is analogous to reinforcement learning algorithms in AI (more on this here). When learning capabilities of early AI systems were driven by actual rewards (and not the probability of reward), these systems were unable to defeat humans in games such as chess and checkers. In these games, the reward (victory) is only achieved or lost towards the end of the game, by which point a player has already made several moves. If the player wins, were all the moves made by the player good and hence, should be reinforced? Similarly, if the player loses, were all the moves made by the player bad and hence, should not be reinforced? This can almost never be the case! One blunder can undo the goodness of all preceding moves, or one magical move can undo the negative consequences of the previous ones.

Several years later, AI systems were tweaked to reinforce actions based on probabilistic chances of success at and after each move. If a particular move increased the probability of winning, it would be reinforced even if the successive moves resulted in a loss. This simple adjustment made ever learning AI systems invincible against humans (constrained by biological energy cycles).

This disassociation from the actual reward and the modulation of probabilistic expectations is key. In the absence of rewards (when one feels stuck), it lends us the ability to either not abandon a high probabilistic path (continue exploiting) or chart newer paths in our search for rewards (explore alternatives).

Consumption of alcohol, nicotine and drugs triggers a release of dopamine (explaining their addictive qualities). In the long run, this interferes with our dopamine receptors, making it harder for us to break away from these pleasure-seeking behaviors. Not just intoxicants, but even seemingly innocuous impulsive behaviors such as watching reels (cheap dopamine) can have similar effects, thus becoming compulsive over time. In today’s information-heavy world where a new AI model is released every other week, attention and agency must be preserved. So, I’d go as far as to say that dopamine is neither the pleasure chemical, nor the reward chemical, heck, not even the reinforcement chemical, but the ‘agency chemical’.

Role of curiosity

Just like omission of an expected reward decreases dopamine activity, receiving an unexpected reward increases dopamine activity.

This, in part, explains several tacit traits in humans. Take gambling for instance, where the odds are ever so slightly in the favor of the house. If the odds were stacked 50-50, each time you lose, your probability of winning would become higher. But the odds are closer to 55-45, such that even if you play long enough, your winnings will rarely offset the losses, let alone outsize them. Gamblers know this but still choose to indulge not because they are motivated by a high probability of winning, but rather a low probability of huge winnings (noticed how a game that costs 50 cents to play has the jackpot as a new car or a million dollars?). Couple that with a release of adrenaline and endorphins, and you’ll find gamblers continuing their bad streak even when fully aware of the ramifications.

But wait, if we recall our discussion around how dopamine works from earlier in this article, one aspect remains unexplained. Shouldn’t the behavior of continuing to gamble only get reinforced when the probability of winning is readjusted upwards? But that is not the case. And the only way to explain this is by attributing these actions to ‘curiosity’, where the uncertain and variable probability action is in itself rewarding and consequently, reinforced by a release of dopamine.

To be curious is to display ingenuity and to seek new knowledge, without external motivation. When we pursue these novel experiences, we are not always motivated by a positive result. The pursuit itself is rewarding, with reinforcement linked to gaining understanding of a new subject or method. So, the next time you want to pick a new hobby, consider how the pursuit of it makes you feel, and not just how good or successful you are at it.